Lucien C. Ducret

The Inventor of the Roto-Split

A Better Mousetrap - Inventors Tackle Life with Yankee Ingenuity

By Elizabeth Payne

Staff writer, Fairpress

When Lucien Ducret was rewiring a room in his Norwalk home in 1973, he fashioned himself an invention that not only spawned a new company but also ended up winning him a bronze award at the International Exhibition of Inventors last April, his second showing there. The Roto-Split® was neither sexy or high-tech, just very practical - and novel enough to warrant patent. Since its creation it has been refined over the years with modifications that landed it the coveted prize this spring.

The idea behind Ducret's invention took shape when he learned that the local hardware store had nothing other than a hacksaw for cutting the steel encased BX cable - a method that had been causing some electricians injuries and even more frustration. Confronted with that problem, Ducret's imagination sped into high gear. "Being an engineer," he recalled in a recent interview, "my wheels start turning when I hear something like that. I say there's got to be another way."

As necessity has always been the mother of invention, Ducret researched the matter thoroughly and found nothing but clumsy, aborted attempts at solving the problem. He finally designed his own prototype of a new device that cut through the heavy outer layer without harming the cable inside, quickly and efficiently.

First Roto-Split prototype - top

First model of the Roto-Split sold - bottom

To gauge the market for the then $8.95 instrument, he ran one small ad in The New York Times that elicited more than 500 orders - about 400 more Roto-Splits than he had on hand. So Ducret sent back the checks and asked customer to wait until he could tool up for higher production. Almost 90 re-ordered, and that was the start of the mechanical engineer's Seatek Corporation.

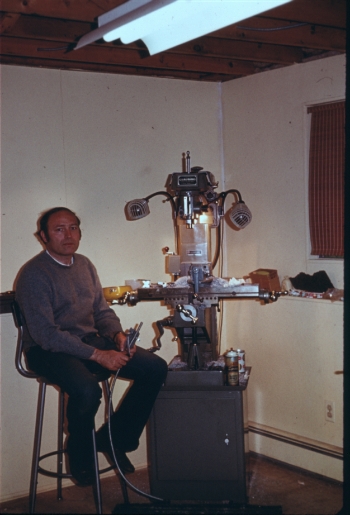

1973 - Making the first batch of Roto-Splits in the basement in Marlin Drive Norwalk, Connecticut

"He's been doing this since childhood," explained his wife, Carol, who also works at the business. "Anything he would put his hands on he would modify to make it better."

Ducret's Roto-Split and patented Swing-Saw are among the many inventions born of Fairfield County minds. Some sound fairly simple, like the new cosmetic powder dispenser for which James Ladd of Rowayton recently received a patent; or the fine-toothed comb designed by a Greenwich pair to pick nits; or the Odor Eaters shoe inserts created years go by Ridgefielder Herbert Lapidus.

Ladd left Chesebrough-Ponds five years ago to form his own cosmetics firm, where he felt he would be freer to develop new ideas. Some large companies, he said, tend to look for quick returns and often shy away from their employees' inventiveness because of the expense and bureaucracy.

"They have the money and they have the manpower, but they don't have the will." Ladd explained. According to the U.S. Patent Office, only about a quarter of the patents issued go to independent inventors, the rest to businesses.

"Because we're small and not as wealthy as a Chesebrough-Ponds, we don't file patents unless we feel they really provide some meaningful protection for the company, because it's just too expensive." Ladd said.

Though not a giant like Xerox or Polaroid, which also were spawned with key patents for marketable products, Ducret's company has now grown from a 400 square foot office to about 7,000 square feet in downtown Stamford. Hundreds of thousands of its number one selling cable splitter, the Roto-Split, are in the field today, costing about $30 each.

Ducret - who worked on the camera shutter for the first lunar landing, to mention just one diversion - has a total of 14 patents (as of 2016 he has 33 patents to his name). And there are "more to come" to continue broadening the company line.

A domestic patent, which takes an average of 22 months to get from filing to acceptance, costs about $1,000 on up, Ladd said. The filing fee itself is normally only $170, but there are other government fees as well as tremendous research and often the need for patent attorneys, which can make the process expensive. Then there are additional fees in each country where an item is patented, something Ladd usually does to ensure no foreign copies come on the market.

Another prolific inventor, Murray Schiffman of Westport, has, like Ducret, been fiddling ever since childhood. His first offering was a flywheel, primitively crafted from cork, toothpicks and flies, to maintain its own momentum when floated in water.

"It would go around and around," said Schiffman, president an co-founder of the lnventor's Association of New England at age 8, Schiffman put together a contraption to muffle the ticking of his alarm clock, which was disrupting his sleep. In 1950, he got his first patent for a wire garment hanger that not only held pants securely, but also prevented creasing. His next patent was for the more elaborate Directomat, once used in the New York subways to help people plot their routes until vandalism got the better of it.

Inventions don't always make it in the market, as both Schiffman and Ducret can attest. "I made a couple of mistakes, like everybody else," Ducret said, describing a "big monster" of a machine he invented years back for measuring and cutting cable, something that never achieved much success despite constant downsizing and other revisions. "I decided this was crazy," he said laughing now. "The challenge was great - I enjoy doing it as an engineer, but it wasn't a moneymaking proposition."

For the small inventor not endowed with company backing, it can be a tough way to make to make a living, said Schiffman. "It's very difficult to be a really successful inventor in terms of money," he said. Schiffman developed the idea for the variable speech control device in cooperation with the Cambridge Research and Development Group in Wesport. "We spent a quarter of a million dollars for the basic patent umbrella and then quite a bit each year to maintain it," he explained.

The Swing Saw, that Ducret has patented in the U.S., Japan, and Common Market countries won an award at the International Exhibition in 1984, but has yet to reach the promising market Ducret anticipates. "It's a long time and it costs a lot of money," Ducret said, "It cost about $60,000 or $70,000 just to tool up."

"Certainly a large percentage of patents don't pay their way," added a patent attorney who recently retired from a major local corporation. "A smaller percentage of patents more or less break even. An even smaller percentage make real money."

The "Sawing" Machine, Geneva Switzerland

Lucien Ducret's first invention, the sawing machine! He "borrowed" his mom's sewing machine and replaced the needle with the blade. Coincidentally soon after this an employee at a Swiss company, Scintilla AG had the same idea with a sewing machine and was credited with the invention of the jigsaw. Something in the water in Switzerland back then? Mom was not happy with the loss of her sewing machine but was impressed with her son's creativity.